Painting Pain as a Therapeutic Outlet

Heather

Bolinder remembers the pain. In fact, she will never forget it. The

trained emergency medical technician and nursing assistant had helped

others in discomfort before, but she had never felt such agony herself.

That is, until that one July day nearly five years ago.

Heather

Bolinder remembers the pain. In fact, she will never forget it. The

trained emergency medical technician and nursing assistant had helped

others in discomfort before, but she had never felt such agony herself.

That is, until that one July day nearly five years ago.Ms. Bolinder was in her garden, tending to her flowers, when suddenly she felt what she now describes as an “excruciating” pain in her back. She couldn’t move. Family members came to her aid and rushed her to the emergency room at a local hospital. It was the first of many visits to hospitals, physicians and specialists as part of a seemingly never-ending effort to get an accurate diagnosis of, and proper treatment for, her pain.

Largely bedridden for more than a year, Ms. Bolinder was forced to give up her job as a nursing assistant as well as her avocation: painting. Even though she knew her art would make for great therapy, she just couldn’t bring herself to pick up a brush—even after a lifetime of painting the nautical scenes that surround her native Cape Cod, Mass. It was a visit to her long-time family practitioner that changed the course of her chronic pain and, ultimately, her recovery.

“I got depressed and lost hope,” Ms. Bolinder says now. “My focus became just getting up and getting through the day. My doctor knows me so well, knows how much painting means to me. He told me, ‘Paint your pain. You’d feel better if you painted what you’re feeling.’”

The physician’s advice took Ms. Bolinder by surprise. She hadn’t thought

about painting her suffering, and wasn’t even sure she knew how to go

about it. In the end, however, these musings brought her to the point

where she could stand in front of the canvas again.

The physician’s advice took Ms. Bolinder by surprise. She hadn’t thought

about painting her suffering, and wasn’t even sure she knew how to go

about it. In the end, however, these musings brought her to the point

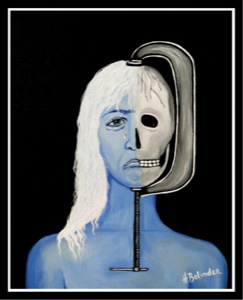

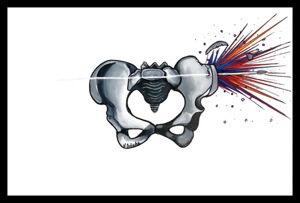

where she could stand in front of the canvas again.And the results have been amazing. In late December, with the help of her fiancé, Ms. Bolinder launched an online gallery of her work called paintingpain.com. She has nearly 30,000 online followers now, many of whom post their own stories on the site. Although the painting did not help her pain—drugs and physical therapy did—it helped her feel less depressed and got her back to work. Using her own pain history and those of the site’s visitors as inspiration, Ms. Bolinder’s paintings attempt to visually describe pain symptoms as well as the emotional effects of chronic pain.

As a professional artist, Ms. Bolinder could sell her work (her nautical-themed paintings have been shown and sold in local galleries), but that’s not part of the plan, at least not for now. Her goal is to partner with medical professionals in the pain field to use her work to educate patients and their families on chronic pain and its management. Recently, she has been working with Christopher Clough, a physician assistant and pain specialist at PainCare, a pain clinic in New Hampshire. Mr. Clough also has started his own Web site called medicalspeakinenglish.com, which is designed as a patient education resource.

“Heather’s paintings give a voice to pain patients,” Mr. Clough told Pain Medicine News. He believes her work “captures the essence” of what patients experience and that the added insight can only help chronic pain sufferers.

Ms. Bolinder’s partnership with Mr. Clough and her efforts to use her

art for the good of patients with chronic pain remain works in progress.

She’d love to create a “visual scale” that patients can use to describe

pain symptoms and their severity, something that would replace what she

calls the “outdated” numeric rating scale. For now, however, painting

pain continues to be therapeutic, both for her and many of those who

visit her site.

Ms. Bolinder’s partnership with Mr. Clough and her efforts to use her

art for the good of patients with chronic pain remain works in progress.

She’d love to create a “visual scale” that patients can use to describe

pain symptoms and their severity, something that would replace what she

calls the “outdated” numeric rating scale. For now, however, painting

pain continues to be therapeutic, both for her and many of those who

visit her site.“I have a vision that I will be able to do a traveling show with my work and that a [pain specialist] will come and talk about what pain feels like,” Ms. Bolinder notes. “For patients, [chronic pain] is a constant mind journey to, one, not be depressed and two, to continue doing what you love to do. Through my art, I’m able to reach people who are going through the same thing I did. I tell them we’re in this together and it’s so much easier when you have a team.”

—Brian P. Dunleavy

Reprinted from Pain Management News

Comments

Post a Comment